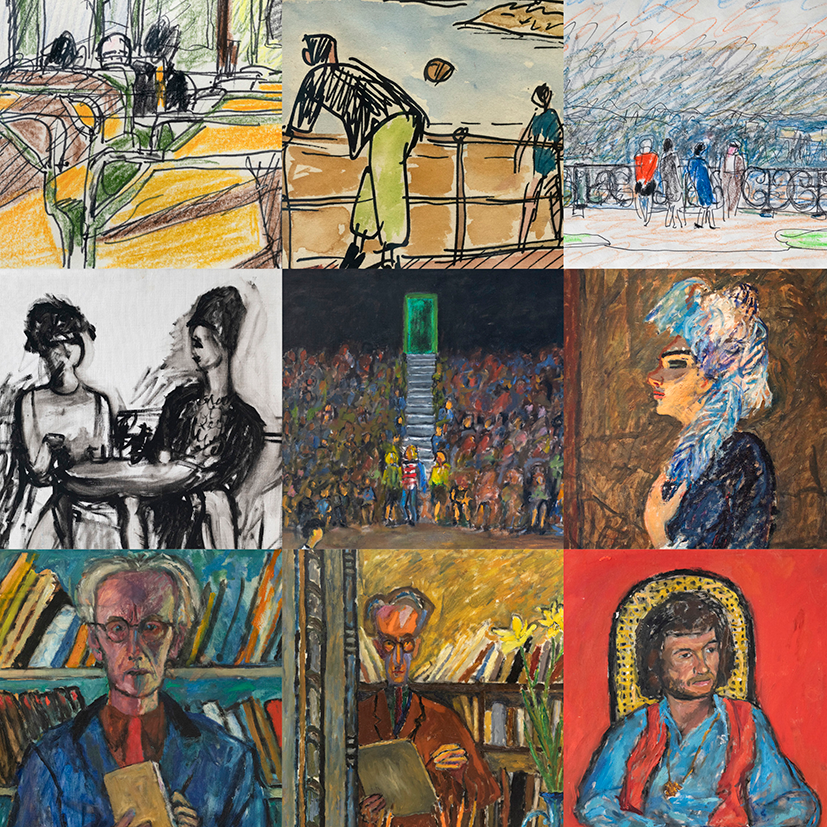

The last time Czapski personally displayed his paintings in Poland was in the summer of 1939 at the Institute of Art Propaganda in Warsaw, during the “Still life in Polish painting” exhibition. After the outbreak of World War II on 1 September, he was called up as a reserve soldier and as soon as 27 September, he was taken prisoner by the Soviet Army. And so began his “journey” through the camps: Starobilsk, Yukhnov (Pavlishtchev Bor), Gryazovets. He was not killed in the Katyn Forest with a shot in the back of the head. He ended up in a group of 395 captives who survived from among more than 22,000 prisoners of Soviet camps. Sketches in his war journals and portraits of his fellow prisoners have survived from that time.As a soldier in Anders’ Army, searching for missing prisoners of war and later standing up against the lies about Katyn in the international arena, he could not return to his homeland after the war. He stayed in exile, in France, co-creating the Parisian “Kultura” magazine. Whenever he could, he sketched, painted, and wrote about literature and art… with palette in hand.After his relationship with “Kultura” became looser in the 1960s, he lived mainly by painting. He supported himself and his sister Maria. They rented two small rooms on the first floor of a villa for which the Literary Institute publishing house had received loans and donations from aristocrats thanks to his connections ten years earlier. Once a year, he tried to organise an exhibition to sell his works. He wrote about himself that he became “an active painter”: as the organiser of his own exhibitions, he paid for booking Parisian galleries, sent out invitations, and took care of the promotion, searching for French critics who would be willing to write a note about him for a newspaper. It was primarily his friends and acquaintances that visited these exhibitions, they bought drawings and paintings. Everything changed when a Swiss man named Richard Aeschlimann – who learned about the artist thanks to Vladimir Dimitrijević – took an interest in his works. He funded a modest scholarship for him then, paid out on a monthly basis. He took whatever Czapski painted to Chexbres, where he sold it to the Swiss. This is why Switzerland – even today – has the greatest number of collections of Czapski’s paintings in private homes, including the largest one – owned by Barbara and Richard Aeschlimann.As Czapski wrote to Janusz Marciniak:This country surely has about nine tenths of my works in the hands of four collectors near Lausanne, and Aeschlimann, my art dealer here and also a collector, has all the data, kept with Swiss precision and a great long-standing friendship. If anyone ever wanted to prepare a retrospective exhibition of my art after my death, Aeschlimann’s address will be enough. I owe it to him that I have been able to work for years without organising exhibitions. [1]He always dreamed that his works would also be displayed and viewed in Poland by his friends, family, the young generation of artists, and the Polish people in general. He was particularly hopeful in 1957. News of the Polish thaw had started to reach the editorial office of “Kultura” and the possibility of travelling emerged. Today, we know from documents that certain “kind and friendly” people were sent to visit the painter and talk him into returning to Poland. A permit was issued to organise an exhibition in Poznań, and the museum there bought his paintings. He really wanted to open the first post-war exhibition of 25 of his works at the National Museum in Poznań. He wanted to meet with those who had lived through the war, those he had not seen since 1939. However, Jerzy Giedroyc objected to “this tourism”, as he called it in a letter to his best friend from before World War II, Ludwik Hering. He gave an ultimatum: either Czapski will go to Poland and not come back to the seat of “Kultura” or he will stay and life will go on as usual. The artist’s hope of visiting Poland died. Still, the exhibition was also presented in Kraków, where Hering saw it.From the preserved correspondence, among others with the director of the National Museum in Warsaw, Stanisław Lorentz, we know that in 1958, Czapski was promised another exhibition and the National Museum readily purchased his works. In 1960, he donated one of them to the museum himself (it had been part of the collection from 1958). The exhibition was never organised, though. De-Stalinisation turned out to be pure fiction, and the Polish thaw – a myth. During the Polish People’s Republic, the name of Józef Czapski was included in a special list of people subject to a total ban on publication.It was not until 1986 that a big exhibition of Józef Czapski’s drawings and oil paintings was organised at the Warsaw Archdiocese Museum. The 90-year-old artist could not appear, however. This time, the obstacle was his old age. He sent an audio tape with a recording of his voice, thanking those who enabled his works to be presented to the Polish people again: “Throughout my entire life, I have dreamt about exhibiting in Poland. Since 1939, I haven’t had one exhibition in Warsaw, in Warsaw where I used to paint for ten years and which used to be my city”[2].In spite of the progressive loss of his eyesight, he painted almost until the end of his days. His works are extremely diverse – from academic drawings, through endless still lifes, to sketches filled with quick notes, drawings intended to freeze the vision, the enlightenment, in order for it to be transferred to an oil or acrylic painting later.“There are days when I am literally flooded with visions of paintings that exist in me, seen in nature, with such power that I cannot doubt it. But when I come home and start painting, I can immediately see a huge difference between what I want and what I can do,” he wrote to Jean Colin d'Amiens.[3]Czapski had a very critical attitude towards his works, yet in this criticism, he was faithful to his vision of painting immersed in nature: in people’s faces, in a bottle, bowls, a vase, a cityscape and a rural landscape… This “quiet life” surrounding him was hiding the dread which he tried to show. Thanks to the trust that the National Centre for Culture enjoys and courtesy of the owners who lent the exhibits, at this exhibition, we can present works never before displayed to the public.One of the paintings is a landscape with an autumn view of the Tatra Mountains. It is one of Czapski’s few preserved works from before World War II. Thanks to unique records, we know that it was given to Helena Dadejowa, and was later owned by Hanna Mycielska.Another one is the portrait of Wacek Kisielewski painted during the pianist’s stay at the seat of the Parisian “Kultura” magazine in 1969. It is the only painting known to me that is signed with a pseudonym: “L. Bonnet, 69”. The sound of the name Czapski is similar to the word czapka, which means a hat in Polish. The painter used this pun in his pseudonym so as not to put those who would take the artwork to the Polish People’s Republic at risk. In Czapski’s journals, we can find other sketches connected with the figure of Kisielewski. He also drew Marek Tomaszewski, who was part of the unforgettable piano duo, Marek and Wacek, alongside Kisielewski. Together, they would often visit the seat of “Kultura” in Paris and… Czapski upstairs.In 2016, I met Katarzyna Skansberg, who told me how she met Czapski and who he was to her. It was the first time I have heard the story about the staging of Kurka Wodna [The Water Hen], about painting the Governor. We bring back that wonderful memory in this catalogue.Another painting was a gift from Elżbieta Łubieńska, the painter’s niece, to Leszek Czarnecki, an archivist, who supported Czapski by staying with him and having conversations with him until his death. The painting was later given to a friend in France and today, it is in Poland. It is the first public display of this work.And another, a special one that Czapski wrote about in 1989:My latest canvas is a piece of a tablecloth and a piece of a red dressing gown on that table. I used it to paint a still life, the best one so far today I think, which I gave to E., so you will see it. My best sister-in-law, who also paints, said to me: “There are painters who are called, for instance, Painter of Christ’s crown of thorns or Painter of the Madonna, but you will be called Painter of rags.” I would really love to deserve this nickname[4].We also present the matching sketch, which is owned by a different person. At this exhibition, they will “meet” for the first time in years: the drawing and the painting.It is impossible to tell the story of each painting presented at the exhibition here. The works of the artist, who lived for over 90 years, are scattered all over the world. Paintings and drawings can be found at public institutions in Poland, but also in Switzerland, at the offices of the French authorities, at a university in Spain, and in museum collections in the United States. Most of them are in private hands – in Switzerland, France, Germany, Belgium, Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Denmark, Portugal, Brazil, Spain, Belarus, and Ukraine, and even in Russia and Japan… and certainly in Poland.“Please mention that I left Poland in 1939, that having painted here for years, I have dreamt, truly dreamt that these paintings and my writing would return to Poland one way or another because in spite of all the bigger and smaller wars us Kapists fought, I feel rooted solely in the Polish tradition, and even Stanisław Witkiewicz has always been on my shelf, right by my side,”[5] Czapski wrote.His dream is coming true. An increasing number of works are coming to Poland, among them one of the larger private collections owned by Jolanta Wańkowicz and Gilles de Boisgelin, which arrived at the Kurozwęki Palace in 1995 from a castle in Brittany and is permanently exhibited in a specially prepared gallery space at the Popiel family museum.Józef Czapski is the only Kapist in Poland today to have his own biographical museum. Called the Józef Czapski Pavilion, it was built in 2016 and financed from state resources and foreign funds. Neither Cybis nor Waliszewski, whom Czapski himself considered to be the most outstanding artists of their joint group, K.P., has a similar place. In 1958, Czapski wrote to Jean Colin d'Amiens about the opinions he heard about his paintings and drawings during the vernissage at the Bénézit Gallery:David came – he violently attacked my painting, “Very powerful”, but he attacked it only as an art dealer: “Ugly women! They do exist, but it’s impossible to sell this!”. Me: “I expected to hear criticism of painting from you”. David: “I am a buyer and I’m too old to risk it”. Green[6] – he came politely, exclaiming how gloomy my painting was, “worse than my books”. A moment later Cassou[7] – calling out: “Wonderful painting! How amusing and full of humour!”.[8]And so may everyone visiting the exhibition at Kordegarda. The Gallery of the National Centre for Culture voice their own opinion about Józef Czapski’s painting.Elżbieta Skoczek, curator of the exhibition, Director of the Józef Czapski Festival. Holder of a Scholarship of the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. Since 2016, she has been popularising the oeuvre of Józef Czapski, publishing articles at www.jozefczapski.pl and czapskifestival.pl. She is preparing a catalogue raisonné of Józef Czapski’s works.[1] Józef Czapski, Listy o malarstwie [Letters on Painting], Poznań 2019, ed. Mateusz Bieczyński, Janusz Marciniak, 49.[2] Czapski’s words recorded on a tape and played back on 6 May 1986 during the vernissage of his exhibition “Czapski. Painting and drawing at the Archdiocese Museum”. The exhibition was accompanied by a display of contemporary painting entitled “Being together” at which the works of Jacek Waltoś and Zbylut Grzywacz were presented, among others.[3] “Czapski-Colin. Myślę, że wiem co najważniejsze” [Czapski-Colin. I Think I Know What Matters Most], Oficyna Naukowa i Literacka t.i.c. 1992.[4] From a letter to Janusz Marciniak, January 1989, in: Józef Czapski, Listy o malarstwie [Letters on Painting], Poznań 2019, ed. Mateusz Bieczyński, Janusz Marciniak, 49, p. 72.[5] From a letter to Janusz Marciniak, 1 August 1986, in: Józef Czapski, Listy o malarstwie [Letters on Painting], Poznań 2019, ed. Mateusz Bieczyński, Janusz Marciniak, 49, p. 14.[6] Julien Green – French Catholic writer of American descent.[7] Jean Cassou – French writer and art critic, in the years 1946–1965, he was the director of Musée National d'Art Moderne.[8] “Czapski-Colin. Myślę, że wiem co najważniejsze” [Czapski-Colin. I Think I Know What Matters Most], Oficyna Naukowa i Literacka t.i.c. 1992.Opening: April 28, 2022, 6 p.m.Curators of the exhibition: Elżbieta Skoczek, Katarzyna HaberOrganizers: Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, National Center for Culture, Kordegarda, Gallery of the National Center for CultureHonorary patronage: Ambassador of the French Republic in Poland, Mr. Frédéric Billet, Ambassador of Switzerland in Poland, Mr. Jürg BurriCuratorial guided tour by Elżbieta Skoczek: April 29, 2022 12:00-14:00, June 4, 2022 12:00-15:00Curatorial guided tour by Katarzyna Haber: June 4, 2022 15:00-19:00Curatorial guided tour by Katarzyna Haber during the Night of Museums: 17:00-21:00The Night of Museums: Gallery on May 14, 2022 will be open until 23:00

Our website uses cookies

The website you are visiting uses cookies to ensure security and improve the quality of the service. If you do not agree to their use, please change your browser settings or leave the site.