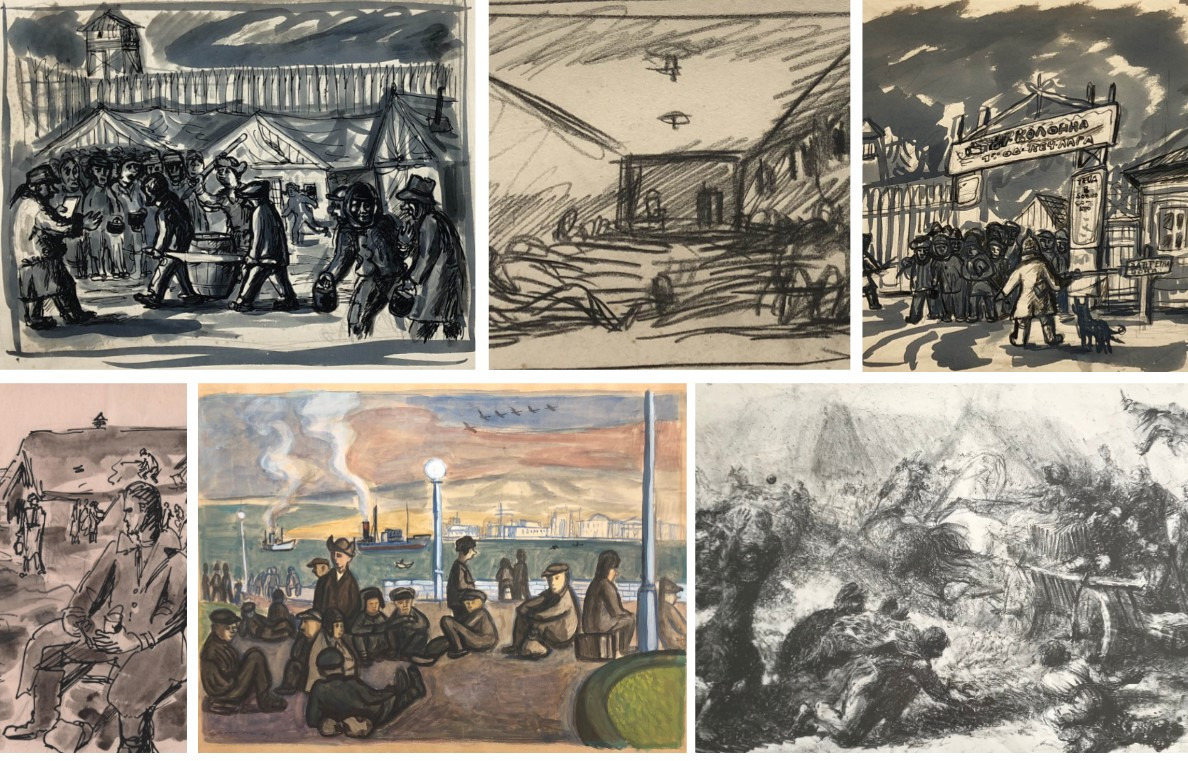

The showcased works created by the artists – Polish soldiers imprisoned in the labor camps in Satrobilsk, Kozelsk, Pavlishtchev Bor, Gryazovets, Kolyma, and Pechora – come from the collections of the Katyn Museum, the Archdiocese Museum, and the National Museum in Warsaw.The collection comprises the miraculously rescued series of drawings preserved and smuggled out of the labor camp in a chess box by its owner, Aleksander Witlib (1910-1982), a prisoner of camps in Kozelsk and Gryazovets and the pre-war teacher and school principal. Portraits, landscapes, genre scenes created by his co-prisoners – Czapski, Turkiewicz, Westwalewicz, and others – are being presented to the wide audience for the first time. We first-time present the works by Adam Kossowski (1905-1986), a graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, the stipendiary of Polish Government, and the winner of the first prize in the contest for wall decorations at the Main Railway Station in Warsaw. Imprisoned in Kharkiv and then Pechora, Kossowski got out of Russia with General Anders’ Army. Due to his poor health, he was transported from Palestine directly to London. In 1943, he started working on a series of pieces depicting scenes from the life of the labor camp. A large number of his drawings enriched the collection of the Warsaw Archdiocese Museum as a donation from the late artist’s wife.The exhibited collection also involved the pre-war graphics by Edward Manteuffel – Szoege (1908-1940) from the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw. As a graduate of the Warsaw School of Arts and the student of Tadeusz Pruszkowski and Władysław Skoczylas, before the war, he established the famous MEWA Atelier which focused on interior design and prepared projects for i.a. the first Polish transatlantic liners. His popular illustrations decorated book and magazine covers. He joined the army in 1939, and as a POW got incarcerated in Starobilsk. He perished under unclear circumstances in Kharkiv.Pieces from the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw, dated to 1933-1937, and therefore, chronologically the earliest ones, present the artist of outstanding skills and sense of form. Classical-inspired book illustrations are kept in the elegant Art déco style. They suggest the artist’s inclinations toward architecture and architectural detail. The depiction of St. Sebastian is far more liberal and expressive. The artist applies wide spots of consistent blackness which makes the piece look like a paper-cut work. How prophetic the death of the saint seems when he is tied up to a tree that glows as if it was lit by the brightness of fire. Or maybe these are only rays of the setting sun?Józef Czapski (1896-1993) taken prisoner by the Soviets in late September 1939 and incarcerated in the labor camp, in his Starobilsk Memoir, describes two profound moments from Starobilsk dwellers’ life – November 11, and Christmas Eve. The water-color piece depicting officers singing Christmas carols is later on glued into his Journal. He recollects how Manteuffel – to a great emotion of the co-prisoners – clandestinely prepares a graphic template which he later uses to imprint the image of the Holy Family on the wafer. Czapski recalls moments when the prisoners gathered in the evening to read together. Those were the awaited whiles that made them believe that they could be saved. It is impossible to assess how many drawings – portraits and ephemeral sketches emerged at that time. With a few and scarce exceptions, all those works perished, as was the case with the history of painting written by Czapski as well as scientific studies of Polish naturalists and biologists, economists, political visionaries, and finally, poetry written by the imprisoned writers.Over sixty works gathered on the exhibition, the variety of pieces that constitute single testimonies to the labor camp art and documentation of life in difficult conditions, strike with the diversity of their authors’ temperaments. Time in the camp, the limit experience, titanic struggle against reality, in which art becomes a scrap of normality and allows to maintain dignity and feel humane. It enables to express one’s emotion, to record the aesthetic enchantment. It lacks the gloomy pathos. On the contrary, we may be left with the impression that artists from Gryazovets seek consolation in beautiful views, in capturing the ephemeral pleasure, relaxing moments on the meadow, or something as simple as reading. There is lots of architecture here, although the portraits of co-prisoners and genre scenes prevail. The artists document the authentic events and capture the moments of normality. And among them, Czapski stands out, tracing the details of physiognomies with bold and cheeky curiosity. He captures and puts the sphere of personal experiences in both lyrical and ironic quotation marks. Works by Zygmunt Turkiewicz (1912-1973) – watercolors painted with skills and talent as great as Czapski’s or tremendous sketches by Stanisław Westwalewicz (1906-1997) are equally attention-drawing. Mood-wise, the works by Adam Kossowski remain on the other pole. The artist worked on the already in London and they brought back the labor camp memories and experiences. Kossowski reaches for the expressionist vivisection. His drawings, gouaches, and water-colors strike with brutality and roughness of contours, ferocity of the form, and at the same time, peculiar naivety, and shift towards grotesque characteristic to Goya. These are pieces of art stained with pathos and poignant pessimism. The most touching are the pencil sketches, instant and darting records of images pushed away and denied by the memory. They freeze the limit experiences and emotions: loneliness, great anxiety, and death. They capture moments of executions – in a journalistic way, one would like to say: almost impersonally. Only the tension in the line and the expressiveness of a fast movement of a pencil reveal the emotional state of the artist. Quill drawings constitute a more lyrical part of Kossowski’s body of work. They introduce a much calmer, nostalgic, and simultaneously affectionate note into this pandemonium of terror. The expressiveness is tamed. Human figures are lees grotesque. If not for the wire entanglements and the silhouettes of armed soldiers, one could assume that the theme is far less atrocious.The exhibition Oblivions encourages to change the optics and approach the Katyn massacre from a different perspective. It individualizes and personalizes the tragedy. From crumbs and scraps, it tries to reconstruct the fate of individuals, sometimes professional artists and at times amateurs. Not always it is possible. About many of the prisoners – the victims of the Katyn massacre, we still do not know a thing. Even here, among those few presented authors, there emerge two artists who are almost anonymous – painter Józef Lipiński (1891–1940), the prisoner of Starobilsk murdered in Kharkiv, and Franciszek Kupka (1915-1940), the prisoner of Kozelsk executed in Katyn. The works presented within the exhibition are the only known testimony to their talent and lives.

Our website uses cookies

The website you are visiting uses cookies to ensure security and improve the quality of the service. If you do not agree to their use, please change your browser settings or leave the site.