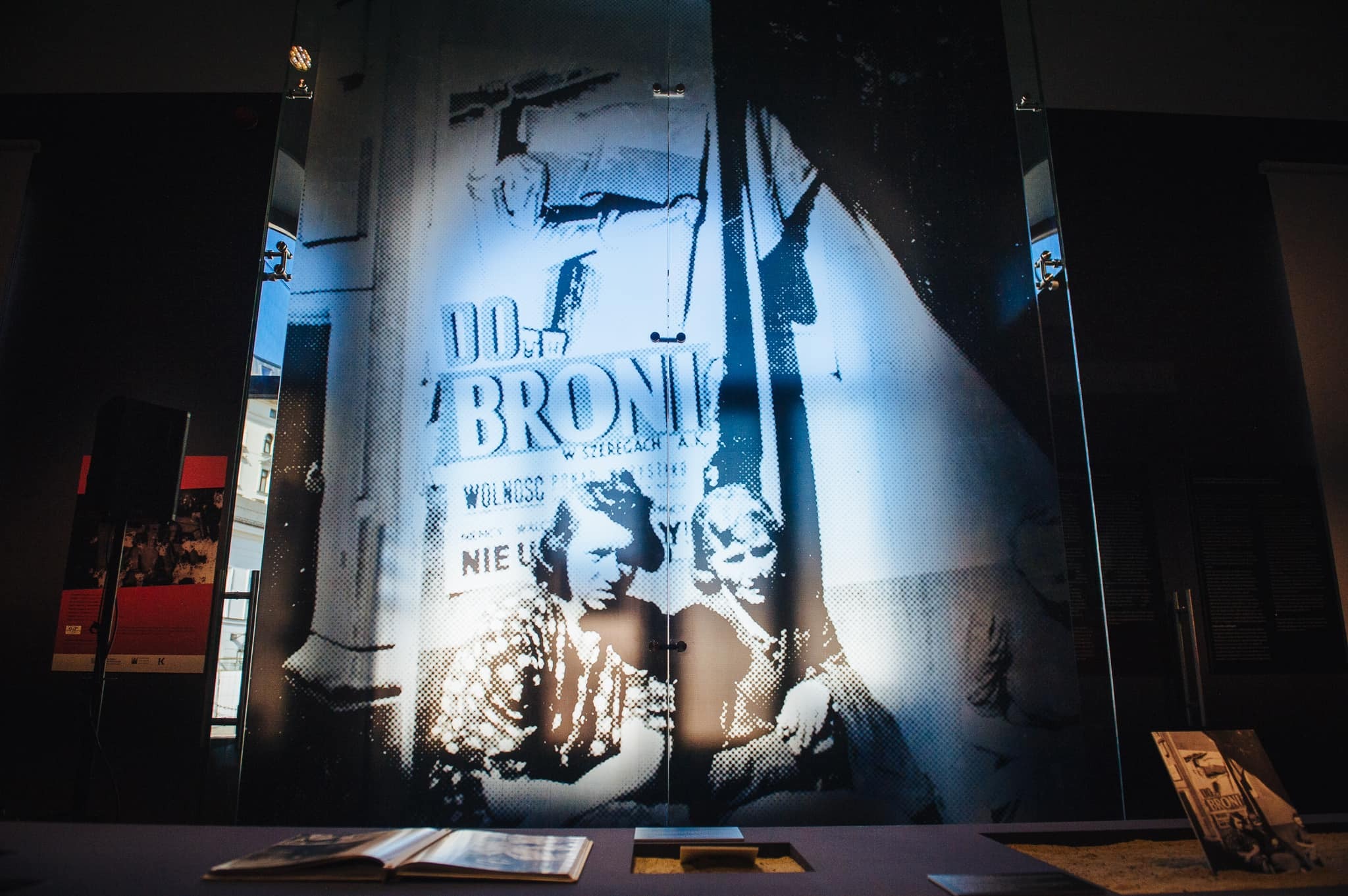

Office of Visual Arts BIP KG AKIf ever great artists depicted hell and the torments of the damned, those paintings seemed to me a conventional setting, so naïve with that horror, with nights of groans and people forming as if one wave of blood and death.Jan Marcin Szancer[1]The outbreak of war in September 1939 interrupted the colourful and diverse artistic life of the interwar period. Artists, both male and female, regardless of their affiliation to specific artistic groups and currents, experienced the dramatic effects of the occupation.Nevertheless, they continued to create, to work, to draw. Art was created everywhere, despite the problems with obtaining materials, paints, canvas, clay. It was created in ghettos, Oflags, prisons, concentration camps. At night, secretly, underground. A special place on this map was Warsaw.Cultural policy of the General Government8 March 1940, Hans Frank, in a special decree, subordinated cultural activities in the General Government to the Department of Propaganda he had created. The guidelines, called “Kulturpolitische Richtlinien”, clearly defined the boundaries of artistic life.It is self-evident that no German office will support Polish cultural life in any way … . County heads should allow Poles to engage in cultural activities insofar as they serve the primitive need for fun and entertainment. … The following should be removed from bookshops, publishing houses and libraries, if it has not already been done: all maps and atlases depicting former Poland, all literary works in French and English including dictionaries, Polish literature in accordance with the lists of banned books promulgated on a regular basis, Polish flags, emblems, portraits of leading persons, pictures with a chauvinistic content from Polish history, if they turn against Germanness, in the possession of public institutions and the association.[2]Janina Jaworska adds another ban from the occupier's orders: “it is forbidden to organise any event imbued with the spirit of Polishness” and “it is forbidden to exhibit paintings with motifs of Polish national thought”.[3] Of the books, only erotic and sensational ones were left, magazines, journals and periodicals were suspended indefinitely. Only those that spread German propaganda and were edited by Germans remained. It was only possible to hold exhibitions and sell paintings clandestinely in antique shops, cafés or street stalls. Instead, German propaganda exhibitions were circulated throughout the General Government. One of them, the most famous, was dedicated to the Germanic legacy in the Vistula basin. At its opening in September 1941, Hans Frank said: “For a long time now, the German has been the very one who has blessed this land with the contribution of his spirit, his art, his culture”.[4]Anyone found in breach of these rules was punished according to the ordinance with prison and a fine, which in practice meant imprisonment, brutal interrogations, a concentration camp and often death.Hunger for artAll the more reason why art became needed like air. Artists, like society as a whole, faced the repressive actions of the occupying forces. Some tried to continue their work to survive, creating for scarce commissions. Others, especially Jewish artists, worked in the ghetto or hid outside of it, while still others were involved in underground activities.A painting shop was set up in Zachęta on the side of Królewska Street, and above it, on the first floor with an entrance from a gate that no longer exists today, were the offices of the Fine Arts Society. … In addition to the office, there was a painting salon … . The demand for works of art and antiques during the first period of the occupation was explained by a flight from cash and the investment of money in objects of value. From time to time, Germans would come here to buy mostly Warsaw-themed paintings to send to their families as souvenirs from the occupied country[5].Grzegorz Załęski, a.k.a. Kula, one of the underground authors, wrote:In the General Government, under the most horrible terror known in Polish history, there were daredevils who risked their lives to publish underground periodicals… satirical ones … . However, one had to be in maltreated Warsaw at the time to understand that the atmosphere created by the occupiers with their constant restrictions, an atmosphere leading inevitably to doubt and apathy, was extremely dangerous for the Polish idea of struggle.[6]Periodicals accompanied by drawings and jokes were created by hand, typed, reproduced and printed, engraved in wood and etched in zinc.The public needed Polish art. Stanisław Tomaszewski, a.k.a. Miedza, recalls in “Benefis konspiratora” that he managed to publish his first volume of poems (patriotic songs) with drawings as late as the autumn of 1940. The whole edition quickly disappeared. However, such actions carried serious consequences. The printing house was quickly exposed and its owner murdered by the Gestapo.[7]UndergroundHans Frank, head of the General Government, at a conference on German policy towards Poles on 14 December 1943, said:There is a certain point in the country that is the source of all misery. It is Warsaw. If there were no Warsaw in the General Government, then the difficulties we face would decrease by 4/5. Warsaw is and will continue to be the focus of all disorder, the place from which unrest spreads throughout the country.[8]In Warsaw, artists joined the fight against the occupying forces. Some – like the esteemed graphic designer and educator Mieczysław Jurgielewicz, later head of the Section of Graphic Design of the Home Army's Bureau of Information and Propaganda – fought in the 1939 September campaign. Jurgielewicz survived, but many artists dies at the hands of the Germans early into the occupation. On 23 September 1939, the young and accomplished sculptor Józef Below was bestially murdered by the Nazi troops entering the capital. Karol Tichy, painter, teacher and founder of the ceramics studio at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, died in November 1939, and his studio on Lwowska Street was burnt down in the uprising, like many others. The documentation created by “Miedza” Tomaszewski for his archive was also lost. Only a fraction of his output survives to this day. Mieczysław Kotarbiński, with whom “Miedza” collaborated on the archive of Tichy’s works, was murdered in 1943 in the ruins of the ghetto. Tadeusz Pruszkowski was murdered in 1942. Leonard Pękalski was shot during the uprising in September 1944. Also killed during the uprising were graphic artists Tadeusz Cieślewski (son), Jadwiga Salomea Hładki, Antoni Wajwód.[9] These are just a few of the names among Warsaw’s artists.In November 1940, the Germans established the largest ghetto in Europe in Warsaw. A number of visual artists found themselves there, the vast majority of whom perished, including: Abraham Warner, Henryk Rabinowicz, Gela Seksztajn or Roman Kramsztyk.Continuing artistic work was not easy. From the very first days of the German occupation, many artists lost their livelihoods and had to seek ad hoc work. Artistic life has gone underground. After the closure of the Institute of Art Propaganda and the Zodiac on Traugutta Street, the entire artistic community began to congregate in the basement of Zachęta in Małachowskiego Square. A canteen has even been set up there. These undergrounds created a special atmosphere through their low architecture with arches and small windows. It was always in twilight.[10]This is the recollection of the first days of the occupation by Stanisław Tomaszewski, then a young graphic artist who had graduated from the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts a few months earlier. Right next door, facing Królewska Street, there was a picture shop where German soldiers bought landscapes of occupied Warsaw.In the spring of 1940, the Bureau of Information and Propaganda was established as Branch VI of the ZWZ headquarters. The bureau, known as the BIP, was originally divided into information, press, publishing and distribution departments. When the exccellent organiser Colonel Jan Rzepecki took command of the BIP in October 1940, the structure was reorganised. From then on, BIP consisted of:Secretariat, Department of Current Propaganda, Department of Information, Departments of Civil Resistance, Department of Distribution, “N” Desk, Instruction Editorial Office, Secret Military Publishing House, Military Historical Office and Prison Cell.[11]BIP published numerous magazines, leaflets and brochures. Efforts were made to mobilise soldiers and the public. Information from the world was gleaned from radio listens. Artistic skills were also useful in developing them. Vignettes, titles, illustrations were created. All the underground prints were highly sought for.Wartime artistic lifeThe Department of Education and Culture of the Government Delegation for Poland, established at the end of 1940, provided ad hoc support to the visual artists. The fund and benefits of the Ład co-operative and Społem consumers' co-operative were also used. Under the guise of commercial interests, establishments carried out extensive activities. Among other things, they supported many artists – the graphic artist Tadeusz Cieślewski (son) and the sculptor Franciszek Strynkiewicz, for example, worked on behalf of Społem.Visual artists collaborated with the Department of Information of the Government Delegation for Poland, including: Maria Hiszpańska, Ewa Śliwińska, Zula Wiśniewska, Henryk Musiałowicz, Alfons Karny, Stanisław Tomaszewski. They created works documenting Nazi terror and occupation life. Tomaszewski's shocking, expressive works show street executions and roundups, while series by Maria Hiszpańska or Aleksander Sołtan devoted to demolished Warsaw were smuggled to the West as testimony to German crimes.Antique shops and art salons also played an important role. One of these was Karol Tchorek's Nike Art Salon, located on Marszałkowska Street. Tchorek opened the Salon in 1943 in the former Wedel shop, abandoned after it was burnt down in 1939. The antique trade was in its golden age during the occupation. Tchorek, who knew from his own experience the difficult economic situation of artists during the occupation, tried to help his colleagues by expanding their activities to include exhibitions and sales of contemporary art.The harmful bias of the art trade during the occupation exclusively towards old-school paintings and deceased painters in the absence of any art criticism doomed contemporary art. This psychosis plunged living artists into extreme poverty.[12]Under these conditions, it was necessary … to actively counter … the harmful atmosphere by setting up some kind of artistic institution.[13]The first exhibition was organised on 15 October 1943. Most probably, it was possible to organise around six exhibitions of paintings, sculpture, ceramics and textiles by Warsaw artists during the occupation until August 1944. Among them were also underground activists of the BIP KG AK. At the first exhibition, Edmund Burke showed paintings, while Mieczysław Jurgielewicz and Wiktoria Goryńska, both active in the BIP KG AK, presented graphic works in December 1943. The salon was also a place for meetings and discussions. The interior decoration was designed by visual artists. The activities of the Nike Art Salon were interrupted by the outbreak of the uprising.Warsaw cafes also hosted poetry meetings, performances and exhibitions. Many artists found employment there.The uprisingAdepts of the nine Muses, help us! Musicians, singers and reciters are requested to report immediately to the Department of Propaganda – Warsaw Powiśle[14].It is difficult to determine today, who exactly was a member of the Office of Visual Arts during the uprising. There was no accurate list of artists, and every available source gives different information.What is certain is that was headed by Mieczysław Jurgielewicz, a.k.a. Narbutt, prof. Henryk, and his deputies were the stage designer Kazimierz Pręczkowski a.k.a. Wagner and graphic artist Stanislaw Tomaszewski, a.k.a. Miedza. The office was tasked with the graphic design of posters, proclamations and slogans for the uprising.[15]It was made up of graduates and students of the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, including Leon Michalski, a.k.a. Leon, Wiktoria Goryńska a.k.a. Leti, Jan Marcin Szancer, Aleksander Sołtan, Jan Chrzan, Ludwik Gardowski, Andrzej Jakimowicz and Mieczysław Sigmund. These are sure not all those who worked at or for the office. Grzegorz Mazur mentions 11 people.[16]Janina Jaworska in her book “Polska sztuka walcząca 1939-1945” adds Zofia Siemaszkowa, Józef Makowski, Edmund Burke. “The second branch of Visual Artists was located at 10 Wspólna Street and was headed by Kazimierz Knot and architect Zborowski”.[17]On 1 August, Jan Marcin Szancer and his wife had a modest dinner at an eatery on Krucza Street. “There were a lot of people, all excited, silent. … It was then that the first shots were fired in Napoleon Square”.[18]The moment of the outbreak of the uprising – as “Miedza” Tomaszewski wrote years later – took the inhabitants of the capital by surprise.The “W” Hour found many away from their families, as it was the time when work in factories and offices ended. A large proportion of these people never saw their loved ones or their homes again.[19]Many Warsaw artists took part in the Warsaw Uprising where the events of 1 August found them.The visual artists, who belonged to the underground under the leadership of “Narbutt” and his deputy “Wagner”, developed “stage designs for soldiers’ theatres and interior decoration for soldiers’ inns and the common rooms of the Aid for Soldiers”.[20] Others also came to the Office workshop, by coincidence or in response to the call.The department, located in the city centre, was constantly changing its location due to bombing. He moved from Moniuszko to Boduen, then to Sienkiewicza Street. It was “the point of dispatch for all things art-related – posters, displays, decorations and lettering”.[21]The task of the visual artists was to fight, but also to document events and participate in propaganda actions. Commissioned by the Bureau of Information and Propaganda of the Home Army Headquarters, they created posters, leaflets and illustrations for the insurgent press, most of which was published in the Śródmieście district. They were decorated with vignettes designed for “Biuletyn Informacyjny” by “Miedza” Tomaszewski, and for “Demokrata” with the sign of the Fighting Poland by Henryk Chmielewski. Each fighting district published its own magazines, which were illustrated by artists: Stefan Barciński, Henryk Kulesza (“Baszta”, Mokotów), Felicjan Gdyka (“Wiadomości powstańcze”, Sadyba). The covers of “Barykada Powiśle” (Nos. 8, 9, 13/14, 21, 27) were adorned by excellent linocuts by Ludwik Gardowski.Szancer recalled:We got a new job assignment at WZW, or Military Publishing House. It was located on Chmielna Street opposite Pakulski Brothers in the print shop in the courtyard. Major Kmita, in charge of the WZW, instructed me to write, draw and print “Dodatek Ilustrowany”. We set off into the city with Zosia, she with a reporter's notebook, I with a sketchbook. I made hurried sketches of the insurgents on the barricades, the ruins of the city and in the basements. Then from these sketches, notes, and even more from impressions remembered, because it was impossible to draw under fire or on a barricade, I composed directly on the offset plate.[22]The artists grouped in the Office of Visual Artists stayed in the large hall of the Italian Bank, as their superior Zygmunt Ziółek, a.k.a. Sawa, recalls, where they did not so much design as make visual decorations for the soldier inns in Śródmieście, including the PKO, the Main Post Office and the Adria.They had a lot of work. They were also happy to perform small services at my request, such as. “Leon” (Leon Michalski) painted on the assault cannon Chwat not only the inscription itself, but also the eagle.[23] The artists created numerous posters that were put up by scouts on the walls of the city: “Every bullet – one German” – an appeal to save ammunition By Henryk Chmielewski, a call to arms “To arms in the ranks of the Home Army” by Mieczysław Jurgielewicz and Edmund Burke, or “Warsaw children, we will go into battle” by Tomaszewski, using a fragment of a poem by Stanisław Ryszard Dobrowolski a.k.a. Goliard. The posters kept morale up, acted as information or urged people to take certain actions, as in the case of the poster “By fighting with fire – you defend Warsaw”. The issue of fires was very important to the Home Army command, so much so that, as Zygmunt Ziółek recalls, when “‘Wiarus’ … with a group of insurgents extinguished a fire in the Prudential building, he received the Cross of Valour for it, as for a combat action”.An insurgent post office was organised in early August. It was run by scouts. For its purposes, a competition was held for an insurgent stamp, which was won by the design of “Miedza” Tomaszewski and Marian Sigmund, depicting three insurgents preparing to shoot against a background of the Prudential, the Sigmund column and the ruins of the Old Town. The stamps, made with great care, had five colours – one for each of the districts of insurgent Warsaw. Artists also tried to record the uprising in quick drawings (Leon Michalski, Stanisław Tomaszewski, Jan Chrzan, Aleksander Sołtan or Juliusz Kulesza). Most of the works were burned. Few survived, like Aleksander Sołtan's Warsaw portfolio, hidden in a coal cellar by the author.Looking for images of the Warsaw Uprising, I could not find works by female artists who worked with their colleagues in the studios of the Office of Graphic Arts. This is documented by photographs from Wilcza Street, taken by Jerzy Tomaszewski. The black and white photograph shows a female figure leaning over a table, with posters hanging on the wall behind her. Death, destruction and fires are certainly responsible for the obliteration of traces of women's artistic activity. However, there is also a lack of memories, of stories. This may also be linked to the relegation of women to the background of the war and the characterisation of their role as auxiliary, as Weronika Grzebalska writes about in her book “Płeć powstania warszawskiego”.[24]***The monumental series “Polskie życie artystyczne”, published by the Ossolineum under the editorship of Aleksander Wojciechowski, which began in 1890, interrupts the historical account in 1939 and returns in subsequent volumes from 1944 onwards. This is not the only publication on the history of Polish art that omits Polish artistic life during the Second World War.There was a pause for five long war years. As a result of bombing, collections were lost, the Germans plundered state and private collections and murdered authors and owners.The historical gap was filled by Janina Jaworska, who in 1977 published “Polska sztuka walcząca 1939-1945”. It is the only publication to undertake a broad description of the artistic life and wartime fate of the artists. We may also find fragments of their artistic lives in the memoirs of the artists. One can draw on fragments of biographies written in retrospect over the years. It was indeed a different time. Poverty, fear, wandering and death affected most Poles, including Polish artists.At Kordegarda, Gallery of the National Centre for Culture, we want the exhibition “Office of Visual Arts BIP KG AK” to recall several artists and their works on which the Warsaw Uprising left its mark. They are a document, a record of a moment.But even this small number of works, regardless of their nature, whether propaganda (posters) or utilitarian (vignettes and stamps), or notes and sketches from the battlefield, created in the midst of death and suffering, surprises with their high artistic stature. It is art that is poor in objects but rich in form and quality.James Donald, in his book “Imagining the Modern City”, states: “What particularly interests me is as a category of thought. … They make things happen. The city we do experience – the city as state of mind – is always already symbolised and metaphorised.”[25]Warsaw is a symbol of struggle, martyrdom and heroism and, in this respect, fits in with Donald's concept of a state of mind. It also has a spiritual aspect, emanating from the art of the Warsaw Uprising, created by people and for people intertwined by the knot of life and death.[1] Jan Marcin Szancer: ambasador wyobraźni, eds. H. Gościański, K. Prętnicki, B. Kusztelski, Poznań 2023, p. 31.[2] P. Rozwadowski, G. Rutkowski, Akcja „N”, Warsaw 2016, pp. 43–46.[3] J. Jaworska, Polska sztuka walcząca 1939–1945, Warsaw 1976, pp. 7–8.[4] P. Rozwadowski, G. Rutkowski, op. cit., p. 23.[5] S. „Miedza” Tomaszewski, Benefis konspiratora, Warsaw 1977, p. 19.[6] G. Załęski, Satyra w konspiracji, Warsaw 1958, p. 11.[7] S. „Miedza” Tomaszewski, op. cit.,, p. 28.[8] C. Łuczak, Polityka ludnościowa i ekonomiczna hitlerowskich Niemiec w okupowanej Polsce, Poznań 1979, p. 73.[9] J. Jaworska, op. cit., pp. 23–24.[10] S. „Miedza” Tomaszewski, op. cit., p. 16.[11] P. Rozwadowski, G. Rutkowski, op. cit., p. 9.[12] A. Chmielewska, K. Kucharska- Hornung, Zmagania z Nike: Salon Sztuki Karola Tchorka, [in:] „Konteksty”, no. 4, 2018, p. 106.[13] A. Straszewska, A.A. Szablowska, Polskie życie artystyczne w latach 1944–1960, t. 3: rok 1949, Warsaw: 2012, p. 86[14] „Barykada Powiśla”, no. 9, 15 August 1944, p. 4.[15] G. Mazur, A. Gieysztor, Biuro Informacji i Propagandy SZP, ZWZ, AK 1939–1945, Warsaw 1987, p. 130.[16] Ibidem, p. 346.[17] J. Jaworska, op. cit., p. 118.[18] J.M. Szancer, Curriculum Vitae, Warsaw 1969, p. 254.[19] S. „Miedza” Tomaszewski, op. cit., p. 163.[20] Z. Ziółek, Od okopów do barykad: wspomnienia 1939–1944, Warsaw 1973, p. 448.[21] J. Jaworska, op. cit., p. 118.[22] J.M. Szancer, op. cit., p. 263.[23] Z. Ziółek, op. cit., p. 448.[24] W. Grzebalska, Płeć powstania warszawskiego, Warsaw 2013, p. 73.[25] M. Leśniakowska, Inne czytanie miasta. Brak i addenda jako krytyczne historie sztuki, [in:] Kultura artystyczna Warszawy. XVII–XXI w., eds. A. Pieńkos, M. Wardzyński, Warsaw 2010, p. 313.Author of the text: Agnieszka Bebłowska Bednarkiewicz, curator of the exhibitionAs part of the exhibition, we have prepared for you the "Krakowskie Przedmieście – uprising episodes" guide, which will be available in the gallery.Curator of the exhibition: Agnieszka Bebłowska BednarkiewiczOrganizers: National Center for Culture, Ministry of Culture and National Heritage